FUNDRAISING FOR A CURE

Donating is simple, fast and totally secure. Your details are safe with us and we will never sell them

Pancreatic Tumours

The pancreas is a small but vitally important organ that lies across the back of the abdomen behind most of the other organs in your tummy.

It has two very important functions:

- Firstly it makes enzymes (digestive juices) that are released into your duodenum (the first part of the intestine, just after the exit of your stomach) to enable you to break down and absorb nutrients from your food.

- Secondly, it makes hormones that are released into the blood stream which control the metabolism of sugars in your bloodstream and around your body. Insulin makes your blood sugar levels go down when they are too high and glucagon makes your blood sugar levels go up when they are too low. In most people these hormones work together to keep blood sugar levels in the normal range.

If the pancreas is not working properly these two sets of functions often break down which is why patients with pancreatic problems often get troublesome bowels, lose weight or become diabetic.

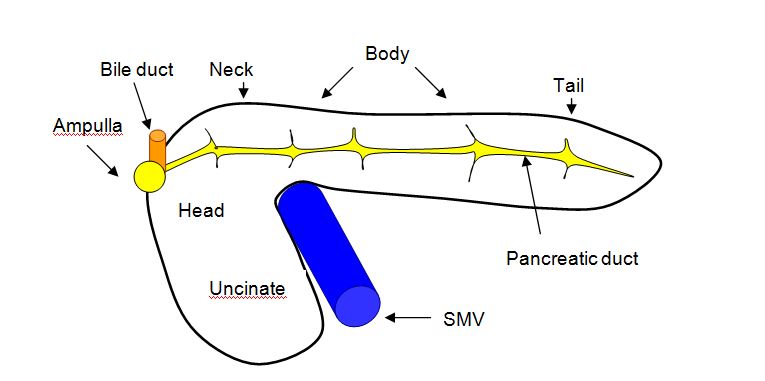

The anatomy of the pancreas is quite complex and a lot of doctors aren’t all that familiar with it so we wont go into detail here, however there are some things that are useful for some patients to know.

There are 6 areas that often get talked about with the pancreas:

- The head of the pancreas

- The uncinate

- The ampulla

- The neck of the pancreas

- The body of the pancreas

- The tail of the pancreas

In particular it lies up against several very large and important blood vessels, one of which, the SMV (superior mesenteric vein) is shown on the diagram above. These arteries and veins supply blood to some of the most important organs in the tummy. Surgery on the pancreas always has to take into consideration the close proximity of these blood vessels and other organs. With some pancreatic operations it may be necessary to remove part or all of some adjacent organs in order to safely remove the part of the pancreas that is diseased.

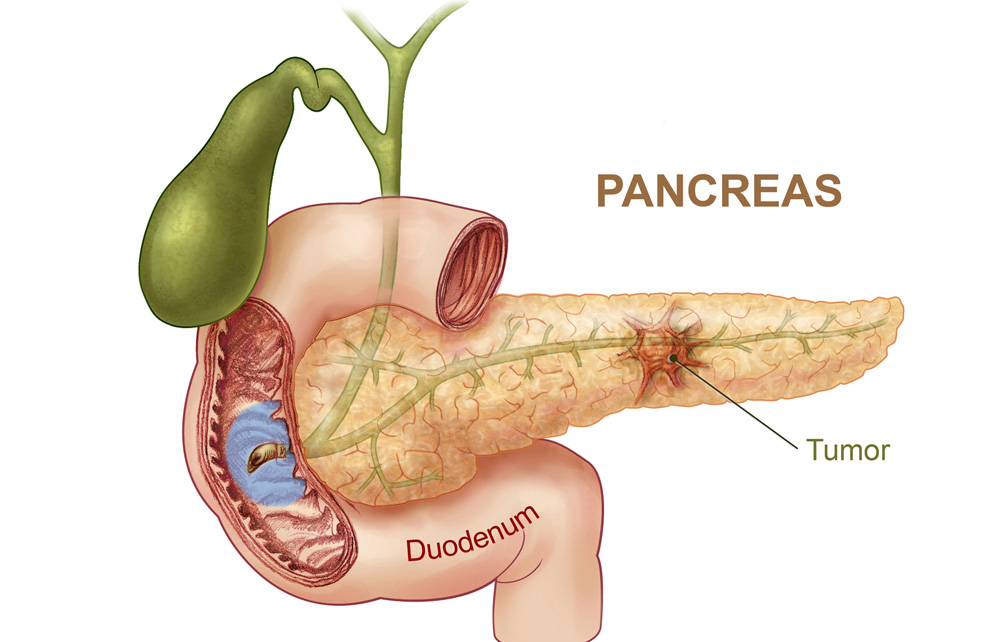

Cancer is a class of diseases characterized by out-of-control cell growth, and pancreatic cancer occurs when this uncontrolled cell growth begins in the pancreas. Rather than developing into healthy, normal pancreas tissue, these abnormal cells continue dividing and form lumps or masses of tissue called tumours. Tumours then interfere with the main functions of the pancreas. If a tumour stays in one spot and demonstrates limited growth, it is generally considered to be benign.

More dangerous, or malignant, tumours form when the cancer cells migrate to other parts of the body through the blood or lymph systems. When a tumour successfully spreads to other parts of the body and grows, invading and destroying other healthy tissues, it is said to have metastasised. This process itself is called metastasis, and the result is a more serious condition that is more difficult to treat.

- Pancreatic cancer: this is the sixth commonest cancer in the UK, it is rare under the age of 45 years, but can occasionally occur in people of any age. The correct term for it is pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. The most common symptoms are jaundice, weight loss, diabetes and back pain. In the UK as a whole less than 1:10 patients are treated with surgery, in our experience this can be pushed up to 1:5, by careful case selection.

- Ampullary cancer: this is usually the easiest of the pancreatic cancers to treat because even very small tumours cause jaundice which means that the cancer is often picked up at an early stage which makes the surgery easier and likely to be more successful.

- Bile duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma): lower bile duct tumours are treated the same as pancreatic cancers because they are hard to tell apart and behave in the same way. This tumour also usually causes jaundice at an early stage. Tumours higher up in the bile duct are considered in the section on liver surgery.

- Duodenal cancer: this rare tumour usually causes a blockage to the exit of the stomach so it is common to get bloating and vomiting as the initial symptoms. Some patients also get anaemia because of blood loss into the gut. It often starts in polyps in the duodenum which start off benign, but as they get bigger become more likely to turn cancerous.

- Sarcomas: these are very rare cancerous tumours that arise from cells in the fat, muscles, nerves or blood vessels in or around the pancreas. The one we see most often is the GIST (Gastro-Intestinal Stromal Tumour) which develops from muscle cells in the wall of the gut. They often grow very slowly pushing other structures out of the way. Due to their slow progression they often do not cause many symptoms, thus by the time patients are aware of them they may be very large and attached to several different organs. However, because of their less aggressive nature it means that surgery to remove even massive tumours is worthwhile because a cure may still be possible. This extensive surgery may involve removal of parts of other adjacent organs (such as liver, kidney, stomach or colon) as well as part of the pancreas.

- IPMN: this stands for intra ductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (which means tumour). These are often very slow growing tumours that arise in the cells lining the ducts of the pancreas, they start off as benign tumours but as they get larger the risk of them turning cancerous increases. We often just keep an eye on small IPMN tumours, particularly in older patients, since they take so long to grow, however if they are enlarging or look suspicious we remove them. They are usually surgically removable, but sometimes require removal of the whole of the pancreas.

- Cystadenocarcinoma is a variant of pancreatic cancer that develops from a type of benign cyst in the pancreas called mucinous cystadenoma, like IPMN the larger these benign cysts get the higher the risk that they will turn into the cancerous cystadenocarcinoma tumour. Although they are often large it is worth surgically removing them if it can be done safely.

- Acinar tumours are very rare slow growing cancers of the pancreas, they sometimes get very big, but can often still be successfully removed, even if they have spread into the liver.

- Neuroendocrine Tumours (NETs) are uncommon tumours that are discussed in detail in the NET section of the website.

- SPEN Tumours (Solid Pseudo-Papillary Epithelial Neoplasm) are extremely rare pancreatic tumours that occur in younger patients (<40 years old), removing them is usually curative.

- Serous cystadenoma is a benign cluster of cysts in the pancreas, it is extremely rare for them to cause symptoms or turn malignant, so we usually leave them alone if we are sure that is what they are unless they have got very big and are pressing on something important.

If you have one of these difficult tumours you must be assessed by a surgeon with a specialist interest in this disease. Your investigations should then be reviewed by your surgeon with the specialist pancreatic multidisciplinary team including radiologists, oncologists, physicians and surgeons. The PLANETS team treat patients with operable pancreatic tumours for all of Hampshire, The Isle of Wight, Dorset and parts of South Wiltshire and West Sussex.

Cancer is ultimately the result of cells that uncontrollably grow and do not die. Normal cells in the body follow an orderly path of growth, division, and death. Programmed cell death is called apoptosis, and when this process breaks down, cancer results. Pancreatic cancer cells do not experience programmatic death, but instead continue to grow and divide. Although scientists do not know exactly what causes these cells to behave this way, they have identified several potential risk factors.

Pancreatic cancers are more likely to exist in men than in women. Smoking cigarettes increases one’s risk of pancreatic cancer by a factor of 2 or 3. Even smokeless tobacco has been noted as a risk factor.

Diet and obesity have also been linked to cancers of the pancreas. Alcohol consumption is also considered a risk factor for pancreatic cancer. Long term, heavy drinking leads to chronic pancreatitis, which is a known risk factor for pancreatic cancer.

Cancer symptoms are quite varied and depend on where the cancer is located, where it has spread, and how big the tumour is. Pancreatic cancer is often called a “silent” disease because it rarely shows early symptoms and presents non-specific later symptoms. Tumours of the pancreas cancers are usually too small to cause symptoms. However, for those who do get symptoms these are the common ones.

- Pain in the tummy. When the pancreas is inflamed (e.g. acute pancreatitis) it often causes pain, this is usually felt in the central or upper part of the abdomen and it often feels as if it is going through to your back. The pain may be sharp, aching or burning in nature.

- Jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes) If the head of the pancreas is enlarged or abnormal then the bile duct may become blocked as it enters the pancreas, this blockage causes a build up of bile which leads to jaundice (a yellow discolouration of the eyes and skin) which is often associated with dark urine, pale, loose bowel motions and itchy skin.

- Pale diarrhoea (Steatorrhoea is the medical term) If your pancreas isn’t working properly then you may get loose, pale, fatty, floating, smelly bowel motions which occur when the pancreas is not releasing digestive juices properly so that the food in the intestines doesn’t get broken down and absorbed properly.

- Weight loss is common with most pancreatic disorders because of the interference with digestion and sugar metabolism.

- Loss of appetite is common with pancreatic diseases and some people get an odd metallic taste in the mouth.

- Diabetes can be caused by pancreatic failure, it is usually characterised by weight loss, tiredness, thirst, blurred vision, increased volumes of urine and drowsiness.

In order to diagnose pancreatic cancer, doctors will request a number of tests as well as personal and family medical histories. The way in which the cancer presents itself will differ depending on whether the tumour is in the head or the tail of the pancreas.

In general, when making a pancreatic cancer diagnosis, doctors pay special attention to common symptoms such as abdominal or back pain, weight loss, poor appetite, tiredness, irritability, digestive problems, gallbladder enlargement, blood clots (deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism), fatty tissue abnormalities, diabetes, swelling of lymph nodes, diarrhoea, steatorrhea, and jaundice.

It is also common for doctors to administer blood, urine, and stool tests. Blood tests can detect a chemical called carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) as well as CA 19-9 – a chemical released into the blood by pancreatic cancer cells. Liver function tests check for bile duct blockage.

Several imaging techniques are employed in order to see if cancer exists and to find out how far it has spread. Common imaging tests include:

- Ultrasound

- Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) – thin tube with a camera and light on one end

- Abdominal computerized tomography (CT) scans

- Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) – to x-ray the common bile duct

- Angiogram – to x-ray blood vessels

- Barium swallows to x-ray the upper gastrointestinal tract

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Positron emission tomography (PET) scans – useful to detect if disease has spread

- The only absolute way to make a cancer diagnosis is to remove a small sample of the tumour and look at it under the microscope in a procedure called a biopsy. A fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy is the most commonly used method. A thin needle is inserted into the pancreas through the skin, and the pathologist uses CT scan or ultrasound images as a guide. Another type is the brush biopsy performed during ERCP to gather cells. A laparotomy is sometimes ordered to determine the stage, or extent, of the disease because it provides access to a large part of the abdominal cavity.

Cancer treatment depends on the type of cancer, the stage of the cancer (how much it has spread), age, health status, and additional personal characteristics. There is no single treatment for cancer.

Treatment options include:

- Chemotherapy. This involves using drugs either taken as tablets or in a drip to try and treat the cancer cells by killing them off. If you have a pancreatic cancer that cannot be surgically removed then it is common to give chemotherapy involving one, two or three drugs to try and control the tumour. Some common drugs that are used are Gemcitabine, Capecitabine and Cisplatin. If the tumour is only in one area and has not spread then sometimes chemotherapy can shrink inoperable tumours enough to make them operable (see Yvonne Shepherd patient story). We also give chemo to some people after surgery to try and make it less likely that the cancer will ever come back.

- Chemo-radiotherapy. This is the combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy to shrink down tumours if they are not operable.

- Cyberknife is a form of targeted radiotherapy using a robotic arm to give the radiation very accurately. It is often used in conjunction with chemotherapy

- Nano knife is a type of ablation system where probes are placed in the tumour under general anaesthetic and electrical energy is used to kill the cancer cells. This is a very new treatment which is showing promise for treating inoperable pancreatic cancers.

- OncoSil is a brachytherapy (internal radiation) medical device used to deliver a radiation dose directly into the tumour via an endoscope. OncoSil is used for inoperable pancreatic tumours that have not spread to other areas, in combination with chemotherapy. The aim of treatment is to reduce the tumour size by destroying the cancerous tissue which may lead to some tumours becoming suitable for surgical removal. This device is currently available privately, though not yet on the NHS.

Surgery may be used to remove all or part of the pancreas. If a cancer has not metastasised, it is possible to completely cure a patient by surgically removing the cancer from the body. After the disease has spread, however, it is nearly impossible to remove all of the cancer cells. There are three main surgical procedures that are used when it seems possible to remove all of the cancer:

- Whipple procedure (most common in cancers of the head of the pancreas): the pancreas head, and sometimes the entire organ, is removed along with a portion of the stomach, duodenum, lymph nodes, and other tissue. The procedure is complex and risky with complications such as leaking, infections, bleeding, and stomach problems.

- Distal pancreatectomy: the pancreas tail is removed, and sometimes part of the body, along with the spleen. This procedure is usually used to treat islet cell or neuroendocrine tumours.

- Total pancreatectomy: The entire pancreas and spleen are removed. Although you can live without a pancreas, diabetes often results because your body no longer produces insulin cells.

- Palliative surgery is also an option when the cancer in the pancreas cannot be removed. Often, a surgeon will create a bypass around the common bile duct or the duodenum if either is blocked so that bile can still flow from the liver and pain or digestive problems can be kept at a minimum. Bile duct blockage can also be relieved by inserting a small stent in the duct to keep it open, a less invasive procedure using an endoscope.

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Get informed about the latest news straight to your inbox