FUNDRAISING FOR A CURE

Donating is simple, fast and totally secure. Your details are safe with us and we will never sell them

NETS

What are NETS?

If you have recently been diagnosed with a neuroendocrine tumour (NET) this information will help you to understand the diagnosis and treatment options that may be offered. Being proactive in learning about your disease can help you to better understand the goals of your treatment and allow you to take control of your health.

NETs is the umbrella term for a group of relatively uncommon cancers. Around 4000 new cases are diagnosed every year in the UK but it is often thought that a larger number of people have a NET, but remain undiagnosed. This is because NETs are often slow growing and so the symptoms take time to develop, may be vague, or attributed to more common and less serious problems such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), Crohn’s disease, peptic ulcer disease or gastritis. After the onset of symptoms, a diagnosis can take an average of 3 – 7 years. If NET cancers are detected early in their development, they can often be cured with surgery. At present, however, most NET cancers are diagnosed at a later stage, when they have already spread to other parts of the body. In these cases, they can rarely be cured, although the symptoms can often be managed successfully for a number of years.

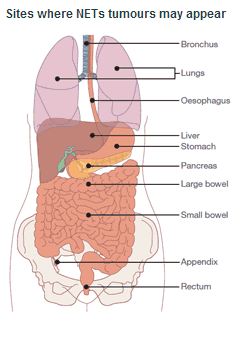

Neuroendocrine cancer is formed in the diffuse neuroendocrine system which is made up of neuroendocrine cells found in the respiratory and digestive tracts. The respiratory tract includes the bronchial tubes and lungs. The digestive tract starts at the mouth and ends at the rectum. Neuroendocrine cells are also found in the endocrine glands, such as the adrenal glands, pancreas, thyroid and pituitary. These cells are also found in the ovaries and testes.

How NETs are formed is still not fully understood. As with all forms of cancer, NETs arise when cells multiply rapidly in the body. Normal cells in our body divide in a controlled manner but in cancer the control signals go wrong. This causes abnormal cells to form which divide quickly resulting in tumour growth.

NETs can be found in several organs of the body but their most common locations are in the lungs and in the digestive system. They were first identified as a specific type of disease in the mid-1800s and the name ‘carcinoid’ was given to them in 1907 to describe a tumour that grew much more slowly than usual cancers. However by the 1950’s it became quite clear that these slow-growing tumours could be malignant and spread from one part of the body to another like other forms of cancer.

The terminology for NETs can be very confusing. The name for NETs has changed over the last few years. Carcinoid is sometimes still used but the more accurate description is NET or Gastroenteropancreatic (GEP) NET. The term GEP came about because the tumours often arise in the cells of the stomach (gastro), intestines (entero) and the pancreas.

Types of Neuroendocrine Tumours

There are a number of different types of NET. They all have a slightly different way of presenting themselves, both in terms of symptoms and how they look under a microscope.

Examples of NETs

- Carcinoids (accounting for 65% of diagnosed NETs): lung, thymic, gastric, duodenal, pancreatic, small intestine, appendiceal, colon, rectal, ovarian and carcinoid tumours of unknown origin (unknown primary).

- Functioning and Non-Functioning Pancreatic Tumours (Some tumours don’t overproduce hormones and may not cause symptoms. These are known as non-functioning NETs. They may be discovered by chance during an operation or a test being carried out for other reasons)

- Multiple Endocrine Neoplasias (MEN is a rare condition caused by a faulty gene, which can be passed on within families from one generation to another (inherited). In multiple endocrine neoplasia, a number of different tumours develop in the endocrine system.

- Gastrinomas (Gastrinomas usually start in the pancreas or the upper part of the small bowel (duodenum). They may produce too much gastrin. Gastrin is a hormone that causes gastric acid to be made)

- Insulinomas (These can occur in any part of the pancreas. The pancreas produces insulin, which controls the level of sugar in the blood. In people with an insulinoma, the tumour produces an abnormally high level of insulin, which causes low blood-sugar levels)

- Glucagonomas (These tumours occur most often in the pancreas. They usually produce too much glucagon, which is a hormone that helps control blood-sugar levels)

- Phaeochromocytomas (Tumour that occurs in the medulla in the adrenal gland. These can be benign or malignant)

- VIPomas (These usually occur in the pancreas. They may produce too much of a substance called vasoactive intestinal peptide)

- Goblet Cell Carcinoids (A rare subgroup of neuroendocrine tumours almost exclusively originating in the appendix)

The place where the NET first appears is called the ‘primary’. However, the NET may spread and be found in other parts of the body e.g. the liver and if this occurs your doctor may refer to these as a ‘secondary’ tumour or metastases.

NETs are still mainly classified according to the area in which they are found:

- Foregut tumours: found in the lungs, stomach, pancreas, gall bladder and duodenum

- Midgut tumours: found in the jejunum, ileum, appendix and right colon

- Hindgut tumours: found in the left colon and rectum

Symptoms of Neuroendocrine Tumours

- Common symptoms include:

- Abdominal pain

- Abdominal swelling

- Diarrhoea

- Rectal bleeding

- Intestinal obstruction (blockage)

- Wheezing

- Constipation

- Flushing

Some NETs produce abnormally large amounts of hormones. These NETs have a related syndrome (Carcinoid Syndrome) which can cause some of the above symptoms and may also lead to heart valve damage and skin changes.

The group of tumours that arise in the pancreas can be classified into two different groups; functioning and non-functioning. The functioning group will produce a number of clinical syndromes that are related to where they originate, for example, an insulinoma will over-secrete insulin and gastrinomas are gastrin-secreting tumours. The non-functioning group which accounts for 30-40% of pancreatic tumours may secrete certain hormones and peptides like other NETs but the release of these chemicals does not cause an identifiable ‘syndrome’ or collection of symptoms. This can make diagnosis difficult and explains why so many causes are picked up incidentally.

For detailed information on the different types of NETs, please follow the links to the NET Patient Foundation patient booklets:

Different NETs Affect People Differently

Different NETs affect people in different ways in terms of how the tumour grows, the symptoms produced, whether or not they spread and how they spread. Gaining histology (what the tumours look like under a microscope) is very important in order to classify the cancer into a type and your healthcare team can then work with you to plan the most appropriate treatment.

Although NETs share similar characteristics, the diagnosis and the way your cancer may behave may be different. The most important aspect of caring for a person with a NET is that the care should be tailored to suit the individual and provided by a specialist in the field of NETs. Your quality of life is paramount and so team work is essential to provide a solid plan of treatment and follow-up.

There has been much research work done by specialist healthcare professionals and progress has been made in terms of understanding these tumours. It is important to ensure that you are seen by these specialists in order to access all the knowledge available. NET cancer care can be complex. For you the journey can encompass not only a whole host of emotions but also a range of investigations, treatments and healthcare professionals. Often there is more than one treatment option available and so there has to be a collaboration amongst all key healthcare professional groups who are making clinical decisions for you. This collaboration is called a multidisciplinary team. This approach is being used across the world in the care of people with NETs and this is what the PLANETS team will provide for you.

The treatment of a NET cancer depends on the size and location of the tumour, whether the cancer has spread, and your overall health.

These are a complex group of cancers to manage, and ideally, a Multi Disciplinary Team will work with you to determine the best treatment plan. The MDT will always have several goals in mind as they formulate your treatment plan.

Treatment Goals

The main treatment goals are listed below:

Main treatment goals

- Remove the tumour by surgery; however, if the tumour has spread, this may not be possible

- Alleviate symptoms

- Control the tumour growth

- Maintain a good quality of life for you

Some of the treatments that are used to reduce or stabilise tumour size and alleviate symptoms are discussed below. To find out more about which treatments are available to you, please speak to the PLANETS (or your healthcare) team.

Surgery

If the tumour is contained in one area (localised), or if there has been only limited spread, surgery is usually the first choice of treatment. If it is possible to remove the tumour completely no other treatment may be necessary.

If the tumour has spread (metastasised), surgery may still be possible to remove the part of the tumour that is producing too many hormones. This is often referred to as tumour debulking.

If a GEP NET or other type of NET is blocking an organ, such as the bowel, surgery may be helpful to relieve the blockage (obstruction). If the tumour has spread to the liver, surgery can be used to remove the parts of the liver containing the tumour. Very occasionally, a liver transplant may be considered.

Surgery may be used throughout a patient’s treatment plan for many reasons, including in combination with other therapies. See the surgery in NETS section for more information.

Somatostatin Analogues

Somatostatin is a substance produced naturally in many parts of the body. It can stop the over-production of hormones that cause symptoms such as diarrhoea, flushing and wheezing. Lanreotide, Sandostatin LAR and octreotide are somatostatin analogues i.e. drugs that copy or mimic the action of somatostatin.

Some NETs produce hormones that can cause other symptoms, for example, patients with a carcinoid tumour may have diarrhoea, flushing, and wheezing. You may have different symptoms depending on the type of tumour that you have. These symptoms can be distressing and often affect your quality of life.

Many NET patients will be prescribed Lanreotide or Sandostatin LAR/Octreotide. The aim of this treatment is to block the release of the extra hormones your body is producing and therefore improve your symptoms. In some cases these drugs have also shown to slow or stabilise tumour growth.

Lanreotide

Lanreotide can be given as an injection every 7-14 days or as a long-acting injection every 28 days. The long-acting injection usually has to be administered by a nurse, either in hospital or by a practice nurse.

Lanreotide is given as a deep subcutaneous injection in the upper, outer quadrant of the buttock.

If you are storing your lanreotide at home it should be kept in the refrigerator, in its original package, at a temperature between 2°C and 8°C; it should not be frozen.

Sandostatin LAR / Octreotide

Octreotide can be given as a short-acting injection two to three times a day, or as a long-acting injection administered by a nurse every 28 days. The short-acting form is injected into the tissue under the skin, either in the upper arm, thigh or stomach. The long-acting form is injected in the large muscle in the buttock.

Octreotide should be stored between 2°C and 8°C; it should not be frozen.

Side effects

There may be some side effects, but it is important to remember that the following are only possible side effects and do not affect all patients:

- Loss of appetite and problems in the gastrointestinal tract (gut) such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and bloating, wind, and upset bowels

- Occasional discomfort at the site of the injection

- After a period of time some patients may develop gallstones as a result of the treatment but your centre monitors this when you have your regular scans

- Short and longer-acting injections can affect blood sugar levels

- You may have raised or lowered blood sugar levels. If you are a diabetic you need to check your blood sugar more often. You may also need fewer diabetic tablets and less insulin.

Any side effects should be discussed with your NET nurse or consultant. Treatment options will always be discussed with you prior to commencement. More information on treatment can be found in the treatment section of the website.

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Get informed about the latest news straight to your inbox